Hi. The following is an excerpt from Tim’s new book What’s Our Problem? A Self-Help Book for Societies. This is the book’s introduction. You can buy the ebook or audiobook or get the Wait But Why version to read the whole thing right here.

Introduction:

The Big Picture

The problem with people is that they’re only human.

– Bill Watterson

Imagine if all of human history were written down in a fat book called The Story of Us.

Humans have been around for a long, long time—according to the most recent estimates, between 200,000 and 300,000 years.1 If every page of The Story of Us covered 250 years of history, the book would be about 1,000 pages long. To take a closer look, let’s tear all the pages out and lay them on the table:

When we really zoom out, we see that most of what we consider ancient history is really just the very last pages of the story. The Agricultural Revolution starts around page 950 or 960, recorded history gets going at about page 976, and Christianity isn’t born until page 993. Page 1,000, which goes from the early 1770s to the early 2020s, contains all of U.S. history.

We’re now collectively venturing into the mysterious new world of page 1,001. This excites me—and also scares me—because of three concurrent facts.

Fact 1: Technology is exponential

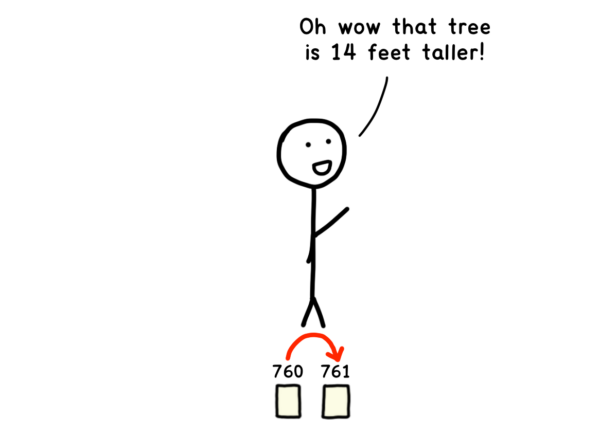

Say we went back to page 760 of The Story of Us, kidnapped someone, and transported them a few centuries forward to page 761. Other than having to find new friends and make some cultural adjustments, they’d probably get along fine, because the worlds of pages 760 and 761 were pretty much the same.

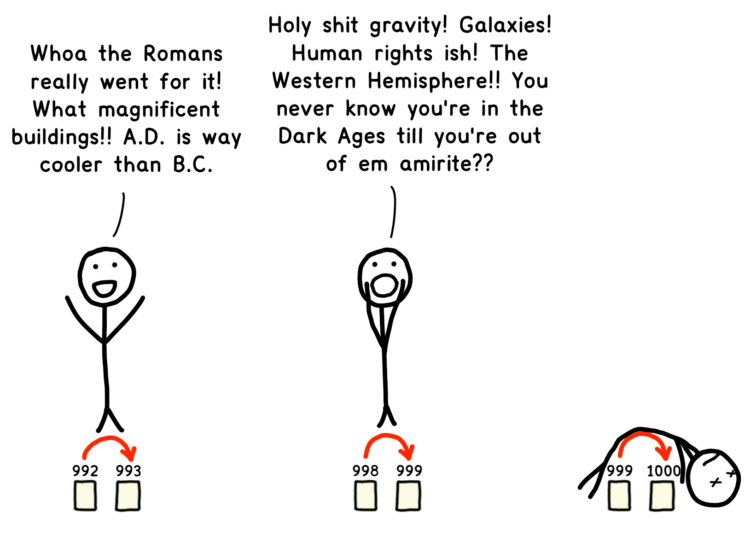

For most of our history, that’s what it would be like to jump forward 250 years to the next page. But the closer you get to page 1,000, the less the rule holds. Like, what if we did the same thing with someone on page 992, 998, or 999?

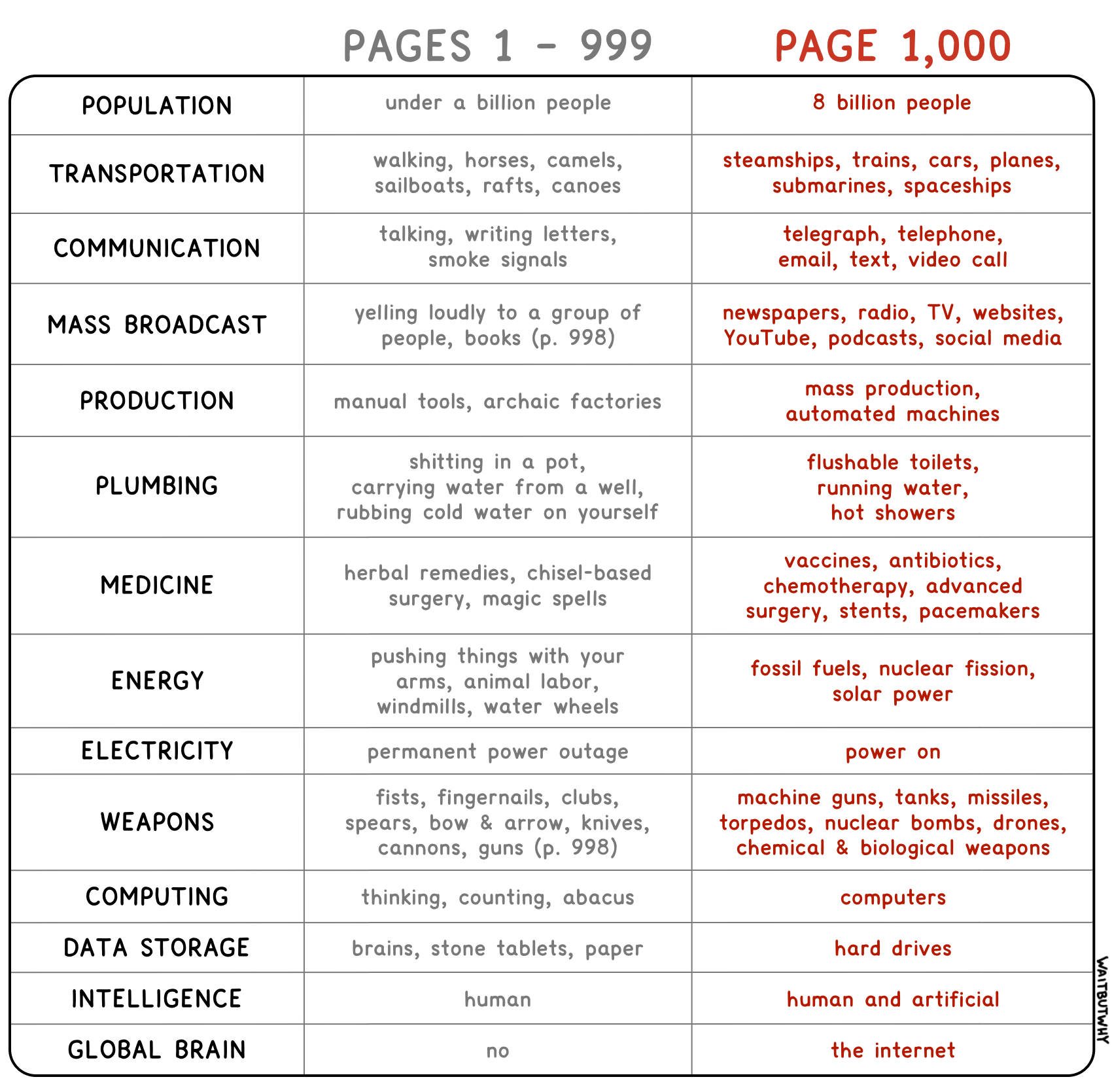

The later you lived in The Story of Us, the more mind-blowing it would be to jump forward to the next page. As you can see, our little person on page 999 was so shocked by the world he saw on page 1,000, he keeled over and died. We can see why when we compare page 1,000 to all the pages before it.

It’s natural to assume that the world we grew up in is normal. But nothing about our current world is normal. Because technology is exponential. More advanced societies make progress at a faster rate than less advanced societies—because they’re more advanced. People in the 19th century knew more and had better technology than people in the 16th century, so it’s no surprise that there were more advances on page 1,000 than on page 999. Over the centuries, this builds upon itself, leading to increasingly rapid progress.2 And ever since the Middle Ages ended, human technology has been advancing on an exponential fast track, leading to a world on page 1,000 that would seem like a totally different planet to humans on any previous page.

Fact 2: More technology means higher stakes

Technology is a multiplier of both good and bad. More technology means better good times, but it also means badder bad times.

On page 999 of human history, the Enlightenment and Scientific Revolution that generated vast improvements in human prosperity also generated an explosion of slavery and brutal imperialism.

Page 1,000, a time of unprecedented life expectancy, wealth, and political freedom, also saw the two most catastrophic wars in history followed by existential threats with the invention of nuclear and biological weapons and the onset of climate change.

As the times get better, they also get more dangerous. More technology makes our species more powerful, which increases risk. And the scary thing is, if the good and bad keep exponentially growing, it doesn’t matter how great the good times become. If the bad gets to a certain level of bad, it’s all over for us.

So far in the 21st century, Fact 1 and Fact 2 seem to be holding strong. The pace of change has been dizzying, with the advent of widespread internet, social media, smart phones, self-driving cars, and crypto, not to mention the dramatic leaps in AI powering many of these advances. The jump in technology from page 1,000 to 1,001 should prove to be even more extreme than the jump from 999 to 1,000—maybe many times more so. This could be unfathomably awesome. We could conquer every problem that ails us today—disease, poverty, climate change, maybe even mortality itself.

But if the catastrophes of page 1,000 were the most devastating yet, what does that mean about catastrophes on page 1,001? The same technology that has made our world magical has also opened a large number of Pandora’s boxes: rapidly advancing AI, cyber warfare, autonomous weapons, and bioweapons, to name a few.

With the stakes this high, we’d want to be our wisest selves. Which is unfortunate, because:

Fact 3: My society is currently acting like a poopy-pantsed four-year-old who dropped its ice cream

I picture society as a giant human—a living organism like each of us, only much bigger. And when I look at the American society around me, I’m not really seeing this:

It looks more like this:

Humans are supposed to mature as they age—but the giant human I live in has been getting more childish each year. Tribalism and political division are on the rise. False narratives and outlandish conspiracy theories are flourishing. Major institutions are floundering. Medieval-style public shaming is suddenly back in fashion. Trust, the critical currency of a healthy society, is disintegrating. And these trends seem to be happening in lots of societies, not just my own.

So what’s our problem? Why, in a time so prosperous, with the stakes so high, would we be going backward in wisdom?

This wouldn’t be the first time. In 1905, philosopher George Santayana issued a warning to humanity:

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.1

The worrying thing about that quote is that philosopher Edmund Burke issued the same warning over a century earlier, in 1790:

People will not look forward to posterity, who never look backward to their ancestors.2

We seem to be having trouble learning an important lesson here.

When we learn a technology lesson, we tend not to forget it. The invention of the integrated circuit in 1959 was a breakthrough that launched a new paradigm in modern computing. This isn’t the kind of thing we later forget, finding ourselves accidentally going back to making computers with vacuum tubes. But wisdom lessons don’t always seem to stick. Unlike technological growth, wisdom seems to oscillate up and down, leading societies to repeat age-old mistakes.

As I look at the world around me today, I worry that we’re on our way toward making some terrible—and preventable—mistakes. When I think about Facts 1 and 2, I picture our societies as giants trudging upward on a mountain ridge toward a glorious future—but as they move upward, the ridge gets thinner and the cliffs on either side grow steeper. The higher we go, the more deadly a fall we risk. When I think about Fact 3, I see those giants losing their composure and becoming more erratic in their steps, at the worst possible time.

If you were reading The Story of Us and turned the page to 1,001, everything would seem to be coming to a head, with many storylines suddenly converging. You’d be glued to the book, needing to find out what happens to this species.

Except we’re not reading The Story of Us—we’re living inside of it, as its characters. We’re also its authors, writing the story as we go along.

Our responsibility is immense. If we can figure out how to get page 1,001 right, Future Us and trillions of our descendants could live high up on that mountain in what would seem like a magical utopia to Today Us. If we get page 1,001 wrong and stumble off those steep cliffs, this might be the last page of the story.

As the authors of The Story of Us, we have no mentors, no editors, no one to make sure it all turns out okay. It’s all in our hands. This scares me, but it’s also what gives me hope. If we can all get just a little wiser, together, it may be enough to nudge the story onto a trajectory that points toward an unimaginably good future.

Hey

Hey.

I know we’re all intense-feeling right now after that intro, but I just want to pause for a minute and introduce myself.

I’m Tim. I spend my time writing a blog called Wait But Why, where I explore all kinds of things—artificial intelligence, procrastination, relationships, aliens, and lots of other random topics that interest me. Then I illustrate the writing with drawings that seem like they were done by a fourth grader but actually were done by a grown-up man. This was all going fine until a few years ago, when something began to nag at me. The society around me seemed to be devolving, and if that kept happening, none of those other topics I write about would matter. If we really were losing our grip on things, every other topic was secondary to that topic. So I dove in.

When I pick a topic to write about, I like to go deep down the rabbit hole. But this topic—what’s our problem?—turned out to be a rabbit hole like no other. As I began to crawl in, I slipped and fell and ended up here.

Normally, I spend somewhere between three days and three months learning and pondering and discussing a topic before I know what I want to say. This one took me six years. When I finally emerged from the extended rabbit hole, I had a new perspective on the world, on politics, on group dynamics, on how we think and why we believe the things we believe. In this book, I’ll share that perspective with you.

In Chapter 1, we’ll get to know the book’s primary tool—a framework that I’ve spent the past six years developing, testing, and refining. I call it the Ladder. The Ladder is a thinking lens—a pair of glasses for the brain to help us better understand the world and ourselves. It’s made me a much better thinker and communicator, and I hope it will do the same for you.

In Chapter 2, we’ll look at the familiar subject of politics through our unfamiliar new glasses. Instead of seeing politics as a mere horizontal axis of left, right, and center, we’ll use the Ladder to supplement the one-dimensional political discussion with a badly needed vertical dimension.

In Chapter 3, we’ll examine the story of our regression: how and why I believe we’ve been slipping down the Ladder as a society.

From there, we’ll look at our current trajectory up close by examining two American stories. First, in Chapter 4, we’ll turn our attention to America’s Republican Party, and then, in Chapters 5–7, a deep dive into the controversial world of American social justice.3 The tired discussions around these phenomena are, I believe, missing the forest for the trees. In both cases, the Ladder will reveal a more interesting and more useful story than is portrayed in popular discourse.

All together, our journey looks like this:

Ready?

This was an excerpt from What’s Our Problem? A Self-Help Book for Societies. To read the whole book, get the ebook or audiobook on all platforms here or buy the Wait But Why version to keep reading here.

More things:

The story behind the making of this book

A.D. is over 2,000 years long, which sounds like a long time, until you realize that humans have been around for over 2,000 centuries.↩

There are exceptions: 7th century Europe (page 995) was, for instance, less technologically advanced than 2nd century Europe (page 993) at the height of the Roman Empire. But most of the time, technology moves in one overarching direction: forward.↩

While many parts of this book aren’t specific to any country, others will seem America-centric. I chose U.S. parties and movements as my case studies because I grew up within them and I understand them best. But the lessons within the case studies are both universal and evergreen. At their heart are common patterns of human nature—the same patterns that likely explain other countries right now. Both the book’s lens and its lessons apply to everyone, everywhere.↩

George Santayana, The Life of Reason, Or The Phases of Human Progress, vol. 1 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1905), 284.↩

Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France, and on the Proceedings in Certain Societies in London Relative to That Event (London: Revived Apollo Press, 1814), 35.↩