After Joe Biden, drugs—specifically psychedelics—were the biggest winner of the 2020 election: Oregon legalized psilocybin mushrooms for mental health treatment; Washington D.C. decriminalized them; and New Jersey introduced a reform bill to drastically reduces penalties for the possession of psychedelics, which later passed.

The changes in these laws follow what Anderson Cooper coined a “psychedelic renaissance,” during a 60 Minutes episode in 2019. Nowadays, everyone from Gwyneth’s Goop gals to the world’s greatest lab partner Michael Pollan is experimenting with drugs that most of us used to only be able to find at a Phish festival. This widened acceptance is generally considered a step in the right direction. After all, studies testing whether psychedelic compounds like MDMA and psilocybin can reduce depression, anxiety, and PTSD have repeatedly shown promising results.

But as attitudes about psychedelics change and access to them inevitably increases, some members of the psychedelic community are pausing to ask themselves an important question: What kind of movement do we want to be? One organization with a vision in mind is Fireside Project, a San Francisco-based nonprofit that has engineered the world’s first psychedelic peer-support line.

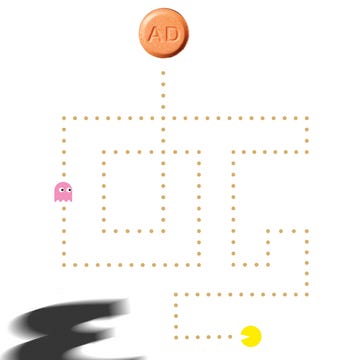

Think of a psychedelic peer-support line as a hybrid of a mental health warmline that people can call or text to receive emotional support during a time of need, and a Reddit thread about peyote-induced visuals. It’s essentially a digital tripsitter that anyone with the wits and wherewithal to use a phone while blitzed can access. Fireside’s mission is simple but surreal: “Help all people minimize the risks and fulfill the potential of their psychedelic experiences.”

According to Fireside co-founder Joshua White, that “all people” bit is an important detail. “When we think about psychedelics, often there's a certain person that comes to mind,” he said when we spoke earlier this spring. “We’re very intentional about saying all communities, all people.” In other words, Fireside isn’t just for your friend from college who smells like a head shop; nor is it only for burners and yogis, or the new age, attention-hacking microdosers of Silicon Valley. Those folks are free to call in, of course, but they aren’t who White had in mind when he set out to build Fireside. Rather, he was hoping to help individuals who might not have the means to safely access and consume psychedelics within the very expensive, burgeoning medical model. (If and when the FDA approves MDMA for the treatment of depression and anxiety, it could cost anywhere from $12,000 to $20,000, by one estimate.)

What White wants to do is create a low-threshold alternative to the walled-off medical model that looms over the psychedelic community. His hope is that Fireside will be one part of a “mycelial network” that includes multiple free psychedelic therapeutic services, which can step in and provide assistance to the many people who studies have shown are increasingly using psychedelics to self-medicate. To help ensure that Fireside’s services are highly accessible, White solicited donations from members of his community. He also received funding from the organic soap company Dr. Bronner’s. Thanks to that money, the Fireside line is free and open to any individual within the United States. (For its first year, Fireside will operate during select hours five days a week. If things go well and additional funding comes through, it will operate 24/7.)

Starting April 14, anyone who is having a psychedelic experience can key in Fireside’s number and text, chat, or speak live with one of Fireside’s 30 trained volunteers. That includes people who are in the midst of a trip, looking to process a past trip, or currently supporting someone through an experience (for instance, a tripsitter who is unsure of how to create a calm environment for a friend). The callers can remain anonymous if they like and will not be asked what substance they are on. (If someone calls for reasons unrelated to a psychedelic experience, Fireside will refer them to other resources.)

For those who have had the humbling experience of tripping without a safety net, the essentialness of a service like Fireside is all too obvious. Put simply, things can get intense fast. Someone who can reassure you that, yes, your hands look normal, and, no, your houseplant isn’t giving you side-eye, is often what prevents a trip from going sideways. And in case things do go sideways—psychedelics can surface powerful, sometimes painful memories or visions—Fireside’s volunteers are prepared to help with tips, perspective, and strategies aimed at rowing an individual back to shore and grounding them in the moment. But you don’t have to be having a bad trip to access Fireside’s services. You can also call in to riff on what you are seeing and share the joy that you may find is bubbling inside you.

Join Esquire Select

Crucially, the volunteers are a well-trained and diverse bunch. They represent 14 countries, 11 languages, 16 ethnicities, and a range of gender and sexual identities. Each one of them has undergone 36 hours of training with Fireside’s Support Line Director, Adam Rubin, and its co-founder and Cultivator of Beloved Community, Hanifa Nayo Washington. The sessions Rubin and Washington lead focus on practical skills like reflective listening, and sociocultural topics like systematic racism, oppression, and equity, so that the volunteers are prepared to “meet people where they are at,” said Washington.

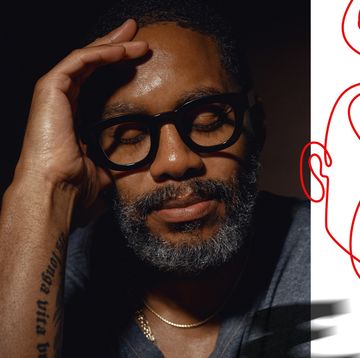

Having an inclusive class of volunteers that represented the entire United States was Washington’s top priority for Fireside, one born from personal experience. “There are so many things that come up in a psychedelic session,” she explained, before describing the many times she has revisited “the pain and trauma of being a Black woman in this country” while on psychedelics and surrounded by white men. Those experiences, while meaningful, led her to conclude that when it came to creating a welcoming and safe environment for callers, relatability and affinity mattered.

Her understanding mirrors a growing, community-wide realization. Recently, the Chacruna Institute for Psychedelic Plant Medicine launched a Racial Equity and Access Committee, which seeks to ensure that historically marginalized communities have access to and are included in psychedelic research. The field has its work cut out for it; a 2018 analysis of past psychedelic studies revealed that 82 percent of participants were non-Hispanic white and only 2.5 percent were Black.

White and Washington have invested so heavily in their volunteers because they are the heart of the Fireside Project. They give callers the opportunity to enrich their psychedelic encounters through connection and integration, the practice of exploring and synthesizing the insights that arise from a psychedelic experience for everyday life. White described this integration as a “muscle that in a lot of ways has not been flexed before.” Despite being a fundamental element of communing with plant-based medicines in indigenous ceremonies, in American popular culture, the practice of integration rarely occurs outside of wellness circles. As a result, it’s a privilege that few people can access or afford.

White views this as a missed opportunity to make the most out of a trip. “After a psychedelic experience, I feel like there's a light inside of me, and the more I talk to people about my experience, the longer that light stays lit,” he said. The Fireside Project will attempt to expand integration by offering weekly follow-up calls, texts, or live chats to anyone who originally called in during a psychedelic experience. “To have a person who you don't know call you and check in on you every single week to ask about how your integration process is going, will, in our view, revolutionize how integration occurs,” said White.

Now it’s time to put that vision to the test. The stakes are high for Fireside’s two co-founders, who met at Burning Man in 2019 and have since devoted most of their time and energy into creating Fireside. White in particular has a lot on the line. In a leap of faith that he credits ayahuasca and therapy for helping him make, he quit his job as a lawyer to devote himself full-time to the psychedelic community. But as Washington reminded him when the three of us spoke, the cause couldn’t be more worthwhile. “[Psychedelics] have the potential to heal a lot of trauma," she said. "Not having barriers to wellness is super important. It's our birthright to heal.”